By Catholic News Service

SOUTH BEND, Ind. (CNS) — A delegation of black Catholic priests paid a visit to the University of Notre Dame’s Theodore Hesburgh Library in South Bend to entrust the archives there with historical documents about African-American Catholic priests, sisters, brothers, deacons, seminarians and laypeople.

The group visited the archives Oct. 24 in advance of Black Catholic History Month in November. The observance was established in 1990 by the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus.

Members of the delegation Father Kenneth Taylor, a priest of the Indianapolis Archdiocese, who is president of National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus; Precious Blood Father Clarence Williams, caucus vice president and archivist; Father Theodore Parker, a priest of the Archdiocese of Detroit; and Deacon Melvin Tardy, an academic adviser at Notre Dame.

The materials they delivered will be preserved in the library’s archives and be available for study.

Father Kenneth Taylor, president of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus, pushes a cart of archival material earmarked for the Theodore Hesburgh Library on the campus of the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Ind., Oct. 25. Assisting him is Holy Cross Brother Roy Smith of Notre Dame. (CNS photo/courtesy Catholic African World Network) See BLACK-HISTORY-MONTH-CLERGY Nov. 2, 2016.

The three priests were nostalgic about bringing the documentation to Notre Dame because of their personal histories with the university.

“It is hard to believe that we were here as seminarians in 1970, and began the National Black Catholic Seminarians Association. And now we return almost 50 years later as priests. Things have come full circle,” said Father Parker. He had served on the coordinating committee of the seminarians association.

The group’s first meeting at Notre Dame drew 70 black seminarians from across the country. They were the guests of the National Black Sisters Conference, which had formed two years earlier.

Father Taylor, who also was present in 1970, called it amazing to see the return of the historical documents to a place that was instrumental in building the black Catholic movement in its infancy.

“November as Black Catholic History Month is a project of the black Catholic clergy, so this is a perfect time to accept the invitation to place our chronicle with the Notre Dame archives on the American Catholic Heritage,” he said.

The Notre Dame visit was one step toward a greater appreciation of the black Catholic movement to be explored in 2018.

Father Williams, who is chairman of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus’ 50th anniversary committee, said the group was “putting things in place” as the anniversary approaches. The anniversary will mark the beginning of the black Catholic movement that began “with the clergy leading it,” he added.

The priests met with the National Interracial Justice Conference in Detroit the week after the April 4, 1968, assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King in Memphis, Tennessee. “These priests asked that those Negro priests present could gather as a caucus to share their feeling and thoughts of the Negro mood,” said a news release on the delegation’s visit to Notre Dame.

The result of those meetings in the late 1960s “was a statement on the racism of the Catholic Church and the formation” of the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus, said the news release. “The rest is history.”

The clergy caucus has a standing committee to review documents and articles that will continue to build the black Catholic collection now at Notre Dame.

“We are open to the contribution of others who wish to preserve our black Catholic history and invite their participation,” Father Taylor said. “In a special way, we dedicate our efforts in the memory of (Benedictine) Cyprian Davis, who recently died.” The priest was the leading example, he said, about the need “to value the contribution of our unique Catholic journey. He was the keeper of the archives and now that he is no longer here to protect and preserve, we must take up that responsibility.”

Father Davis, who died May 18, 2015, at age 84, was considered the pre-eminent chronicler of black Catholic history. He wrote six books, including “The History of Black Catholics in the United States,” published in 1990. He was working on a revised edition of the book at the time of his death.

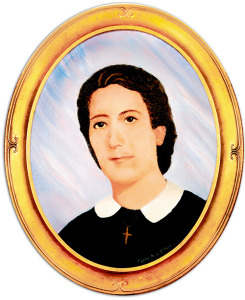

He also had also written what is considered the definitive biography of Mother Henriette Delille, the black foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family in antebellum New Orleans. Her sainthood cause was opened in 1988 and she was declared venerable in 2010.

unveiled a portrait of their founder. The nine-by-four-foot painting by artist Ulrick Jean-Pierre was commissioned by late congregational leader, Sister Eva Regina Martin, SHF, and hangs in the motherhouse. It shows Sister Delille surrounded by the poor she served for her whole life with St. Augustine church in the background.

unveiled a portrait of their founder. The nine-by-four-foot painting by artist Ulrick Jean-Pierre was commissioned by late congregational leader, Sister Eva Regina Martin, SHF, and hangs in the motherhouse. It shows Sister Delille surrounded by the poor she served for her whole life with St. Augustine church in the background.