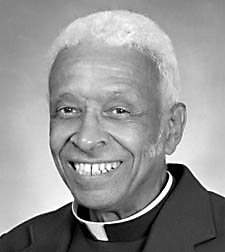

Father Ron Rolheiser

IN EXILE

By Father Ron Rolheiser, OMI

One of the richest experiences of grace that we can have this side of eternity is the experience of friendship.

Dictionaries define friendship as a relationship of mutual affection, a bond richer than mere association. They then go on to link friendship to a number of words: kindness, love, sympathy, empathy, honesty, altruism, loyalty, understanding, compassion, comfort and (not least) trust. Friends, the dictionaries assert, enjoy each other’s company, express their feelings to each other and make mistakes without fear of judgment from the other.

That basically covers things, but to better grasp the real grace in friendship a number of things inside that definition need explication.

First, as the Greek Stoics affirmed and as is evident in the Christian spirituality, true friendship is only possible among people who are practicing virtue. A gang is not a circle of friendship, nor are many ideological circles. Why? Because friendship needs to bring grace and grace is only found in virtue.

Next, friendship is more than merely human, though it is wonderfully human. When it is genuine, friendship is nothing less than a participation in the flow of life and love that’s inside of God. Scripture tells us that God is love, but the word it uses for love in this case is the Greek word agape, a term which might be rendered as “family,” “community” or “the sharing of life.” Hence the famous text (“God is Love”) might be transliterated to read: God is family, God is community, God is shared existence and whoever shares his or her existence inside of community and friendship is participating in the very flow of life and love that is inside the Trinity.

But this isn’t always true. Friendship and family can take different forms. Parker Palmer, the contemporary Quaker writer, submits: “If you come here faithfully, you bring great blessing.” Conversely, the great Sufi mystic, Rumi, writes: “If you are here unfaithfully, you bring great harm.” Family and community can bring grace or block it. Our circle can be one of love and grace or it can be a one of hatred and sin. Only the former merits the name friendship. Friendship, says St. Augustine, is the beauty of the soul.

Deep, life-giving friendship, as we all know, is as difficult as it is rare. Why? We all long for it in the depths of our soul, so why is it so difficult to find? We all know why: We’re different from each other, unique and rightly cautious as to whom we give entry into our soul. And so it isn’t easy to find a soulmate, to have that kind of affinity and trust. Nor is it easy to sustain a friendship once we have found one. Sustained friendship takes hard commitment and that’s not our strong point as our psyches and our world forever shift and turn. Moreover, today, virtual friendships don’t always translate into real friendships.

Finally, not least, friendship is often hindered or derailed by sex and sexual tension. This is simply a fact of nature and a fact within our culture and all other cultures. Sex and sexuality, while they ideally should be the basis for deep friendship, often are the major hindrance to friendship. Moreover, in our own culture (whose ethos prizes sex over friendship) friendship is often seen as a substitute and a second-best one at that, for sex.

But while that may be in our cultural ethos, it’s clearly not what’s deepest in our souls. There we long for something that’s ultimately deeper than sex–or is sex in a fuller flowering. There’s a deep desire in us all (be that a deeper form of sexual desire or a desire for something that’s beyond sex) for a soulmate, for someone to sleep with morally. More deeply than we ache for a sexual partner, we ache for a moral partner, though these desires aren’t mutually exclusive, just hard to combine.

Friendship, like love, is always partly a mystery, something beyond us. It’s a struggle in all cultures. Part of this is simply our humanity. The pearl of great price is not easily found nor easily retained. True friendship is an eschatological thing, found, though never perfectly, in this life. Cultural and religious factors always work against friendship, as does the omnipresence of sexual tension.

Sometimes poets can reach where academics cannot and so I offer these insights from a poet vis-à-vis the interrelationship between friendship and sex. Friendship, Rainer Marie Rilke suggests, is often one of the great taboos within a culture, but it remains always the endgame: “In a deep, felicitous love between two people you can eventually become the loving protectors of each other’s solitude. … Sex is, admittedly, very powerful, but no matter how powerful, beautiful and wondrous it may be. If you become the loving protectors of each other’s solitude, love gradually turns to friendship.”

And as Montaigne once affirmed: “The end of friendship may be more important than love. The epiphanies of youth are meant to blossom and ripen into something everlasting.”

(Oblate Father Ron Rolheiser, theologian, teacher and award-winning author, is President of the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, TX.)