Ordinary Time

By Lucia A. Silecchia

As September dawned, eyes turned to Rome with joy to celebrate the canonizations of two young men – Sts. Pier Giorgio Frassati and Carlo Acutis. In a particular way, many hoped that the holy lives of these two new saints would have a special appeal to young people who would see in them examples of lives well and faithfully lived.

Merely a week later, Sept. 14 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the canonization of another young saint, Elizabeth Ann Seton. I dimly remember this event from my early childhood, and recall similar excitement that she would inspire a world hungry for good examples of faithful lives.

Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton was the first American-born saint to be canonized, a sign that our still-young nation can be the soil from which holy lives spring forth for the glory of God.

As a native New Yorker, I am parochially proud that St. Elizabeth Seton was born in New York City. In addition, St. Kateri Tekakwitha was also born within what would become New York State. Other saints such as Frances Cabrini, Marianne Cope, Isaac Jogues and John Neumann, while not born in New York, contributed greatly to the spiritual and temporal good of my home state. Certainly, not all saints from the United States are from New York! In the past fifty years Elizabeth Seton has been joined by other saints and blessed from across her homeland.

The story of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s short life is well known, but worth reflecting on in this milestone year. She was born in 1774 to a prominent Episcopalian family. Her mother died when she was a mere toddler – the first of many profound losses she would experience. Elizabeth married William Magee Seton, a prominent businessman, in 1794. Together they had five children.

Sadly, their happiness was short-lived. William’s business fortunes declined, and tuberculosis took a toll on his health. Hoping that a change in climate would cure him, they sought refuge with friends in sun-soaked Italy. Alas, William died there in 1803, leaving Elizabeth a young widow with five children aged eight and under. It was in Italy, however, that Elizabeth learned about the Catholic faith and it touched her soul in a bleak season of her life. When she returned to New York, she entered the Catholic Church in 1805 – a decision with a deep cost to her in social circles hostile to Catholicism.

Four years later, Elizabeth and her children came to the Diocese of Baltimore – the premier see in the young United States – at the invitation of Bishop John Carroll. She established both a school and the first American community of religious sisters, the Sisters of Charity of St Joseph.

“Mother Seton,” as she was now known, her children, and the first of her sisters settled in the hills of Emmitsburg, Maryland to build their school and community.

I have often visited Emmitsburg to enjoy the peaceful beauty of the hills she knew and the places she dwelled. What I easily lose sight of is that the rugged beauty of this place was, two centuries ago, harsh and unforgiving. It was in those hills, in a simple graveyard, that Mother Seton buried two of her daughters, Annamaria and Rebecca, who succumbed to illness in the cold. Many of Mother Seton’s first sisters – including other members of her family – also died in those early, desolate years in Emmitsburg.

After losses like these she said, “I am satisfied to sow in tears if I may reap in joy. And when all the wintry storms of time are past, we shall enjoy the delights of an eternal spring.”

Now a saint, Mother Seton truly does “enjoy the delights of an eternal spring.” The community she gathered and the school she founded, at such great cost, continued to flourish. To her is credited the American Catholic school system that, for more than two centuries, has taught generations about both this world and the next.

I vaguely remember watching her canonization on television and discussing it in school. I remember the excitement, on the eve of the United States’ Bicentennial, that an American saint was celebrated beyond the confines of the time and the place she had lived.

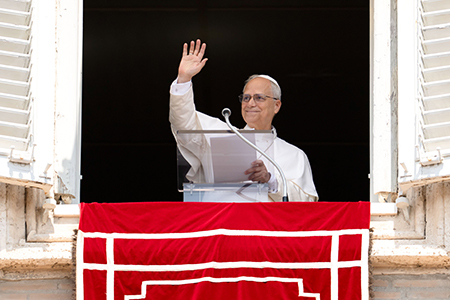

As he proclaimed her a saint, Pope Paul VI said, “Elizabeth Ann Seton is a saint. St. Elizabeth Ann Seton is an American. All of us say this with special joy … Rejoice for your glorious daughter. Be proud of her. And know how to preserve her fruitful heritage.”

Fifty years have passed since then. I was blessed with many years as a student in Catholic schools and have spent my adulthood in Catholic higher education. I have read Mother Seton’s writings, inspired by the simplicity and the strength of this older sister in faith. I have wondered how willing I would or could be in saying “yes” to the labor asked of me, if I knew in advance how high the cost might be.

I have spent time in the hills of Maryland where Mother Seton lived, worked, prayed and died at the age of forty-six, on January 4, 1821. I hope that if time and travel allows, you might find yourself in Emmitsburg someday to walk where she trod, pray where she mourned, see where she taught and pause at the tomb of this “glorious daughter.” More than that, it is a beautiful place to pray for all who serve our church and our nation. May they have the strength, faith and wisdom to “preserve her fruitful heritage” in the hard work of ordinary time.

(Lucia A. Silecchia is a Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Faculty Research at The Catholic University of America. “On Ordinary Times” is a bi-weekly column reflecting on the ways to find the sacred in the simple. Email her at silecchia@cua.edu.)