By Mary Woodward

JACKSON – Back in December, Bishop Joseph Kopacz blessed and dedicated a statue of Servant of God Sister Thea Bowman, FSPA. The statue was a gift from the bishops of the Province of Mobile, which consists of the Metropolitan Archdiocesan See of Mobile and the Dioceses of Jackson, Biloxi and Birmingham. These four venerable dioceses encompass the Catholic Church in Mississippi and Alabama.

Since then, the statue has been seen by a multitude of people from around the South and beyond. We have several pilgrimage groups coming to visit the Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle and the statue throughout this Jubilee Year of Hope.

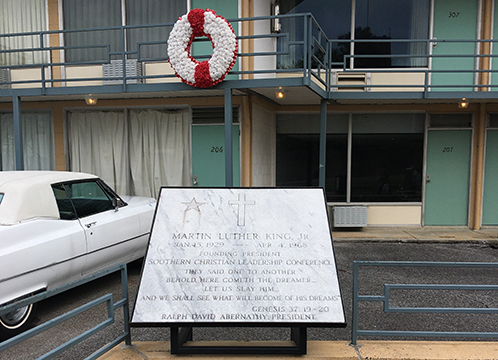

Furthermore, some anniversaries of key events in the history of the region have occurred. March 7 marked the 60th anniversary of what is referred to as Bloody Sunday, when civil rights marchers were attacked on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama; March 30 was the 35th anniversary of Sister Thea’s death in Canton; and on April 4 we reached the 57th anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in Memphis at the Lorraine Motel, which now serves as the National Civil Rights Museum.

Our diocesan archive contains a chronicling of the Catholic Church’s role in the civil rights movement in Mississippi. Bishop Richard Gerow’s diary describes many events and efforts by the local church to be a voice for justice in a very difficult, tumultuous time, including a visit to the White House in July 1963 to meet with President John F. Kennedy and U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy to discuss how the administration could help with the volatile situation in Jackson after the assassination of Medgar Evers in June.

Some of the earliest meetings between local clergy – black and white – happened in our diocesan chancery building prior to 1963. Bishop Joseph Brunini, who had been ordained and appointed something similar to an apostolic administrator to assist Bishop Gerow in 1957 worked alongside Black Pastors, the bishops of the Episcopal and Methodist church, and the local Rabbi to speak out against intimidation and the bombing of black churches.

During this time, Sister Thea would be finishing up her undergraduate studies at Viterbo University in LaCrosse in 1965 and heading off in 1966 to Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., to get her M.A. in 1969 and her Ph.D. in 1972. All the while she was keeping a close eye on her home in Mississippi.

Then in 1978 after Sister Thea had returned to Canton to care for her aging parents, Bishop Brunini invited and hired Sister Thea to serve as the Diocesan Consultant for Intercultural Awareness. From this role she was able to travel and inspire myriads of people by being a beacon of truth, justice and hope in a world in need of such light.

This past week we received word that a biography of Sister Thea by Mary Verrill entitled Thea Bowman: A Story of Triumph has been approved for use in Mississippi schools as a fourth-grade elective textbook for social studies. So, Sister Thea will be able to inspire another generation of young minds.

Looking back to the statue installation, there was a great deal of enthusiasm and interest in Sister Thea’s cause for beatification and canonization. At the reception following the dedication, the desire to form a province-wide guild to help promote the cause and educate others on Sister Thea’s legacy was introduced. In the months since that introduction, we have been in dialogue with Rev. Victor Ingalls, director of the Office of Multicultural Ministry for the Archdiocese of Mobile, about launching the guild this November during Black Catholic History Month.

In conjunction with celebrations in Mobile, the Diocese of Jackson through the Archives and Chancellor’s office will be sponsoring a bus tour to Mobile and Montgomery the weekend of Nov. 15-16. We are calling it The Sister Thea Bowman Jubilee of Hope Tour.

Details will be released soon but the trip will include a visit to Africatown where the Clotilda, the last slave ship, arrived in 1860, 52 years after the international slave trade had been outlawed; after that we will participate in a Black Catholic History Month Mass in Mobile where the guild will be formally launched; then on to Montgomery to visit St. Jude Parish where civil rights marchers were housed during the Selma to Montgomery March in 1965 mentioned above; finally we will tour the Equal Justice Initiative Museum and grounds.

The province guild will be the charter guild for Sister Thea’s cause and will be open to Catholics and friends in Mississippi and Alabama who want to support and promote Sister Thea’s Cause. Other guild branches will be formed around the country as we move forward as well. We still are working on a basic set of guidelines and responsibilities for membership, but we hope the guild will be a place to share the excitement around and the beauty of Sister Thea’s inspiring life and legacy.

Sister Thea Bowman, pray for us!

(Mary Woodward is Chancellor and Archivist for the Diocese of Jackson.)