BOOK REVIEW

By James Tomek, Ph.D

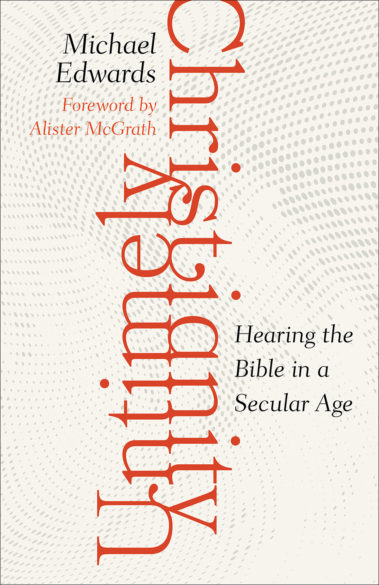

“Untimely Christianity: Hearing the Bible in a Secular Age” by Michael Edwards. Fortress Press (Minneapolis, 2022) 174 pp. $28.00.

“My Lord and my God.”

I was taught to say these words at my First Holy Communion Mass at the Consecration. When the priest raised the Host consecrating it as the Body of Christ, we were to respond silently “My Lord and My God”– the words of our doubting Thomas when Jesus revealed to him the truth of his Resurrection. Biblical scholar and poet Sir Michael Edwards, in Untimely Christianity, translated by John Dunaway, professor of Comparative Literature, praises Thomas’s response as the greatest expression of Faith in Jesus Christ as God in Scripture. (11)

Let’s explore this Faith, hopefully giving some insight in how to read the Bible with Jesus as our guide. Father Kent Bowlds, in Cleveland, is starting a Wednesday scripture study (call (662) 588-2956). I hope these thoughts will inspire us to join.

Knowing Faith for Us Doubting Thomases: An Ars Poetica for Bible Reading

It is “faith above all with all the rest being vague reassurance.” (40)

Translator John Dunaway, himself, a specialist in French literature, tells us that this is an ironic play on words from a Paul Verlaine poem Art poétique.

An ars poetica (Latin) is usually a “direction” on how to compose a work of art – a poem. Here, Verlaine prefers a music feel, letting the reader focus on an adventure of a major human experience. “All the rest is literature” – the curtain line – means all the rest, other than poetry, is just superficiality. Untimely Christianity is an ars poetica on reading and hearing the “Word of God,” redefining our Christianity by treating the Bible as the sacrament of Jesus. Rather than looking for dogma, we follow Jesus as a major poet or artist of God’s “Word” and how his lived incarnate life can be ours. For “knowing” Jesus, the verb connaître may fit better. Savoir is about knowing facts (I know that …). Connaître is more an “acquainted with” or “feel” type of knowledge. Edwards puts “faith” into a connaître type of knowing – more with a feel than a proof – more associated with Verlaine’s music rather than a theologian’s prose essay. A synonym of this “faith” is the grace that God gives us. (31) Doubt is helpful. It is the oxygen needed to get to the way of truth. (40) Jesus helps us doubting Thomases.

Poetry vs Prose – Knowing the Right Time

Art, or poetry, is a tactic where we can bring Hope into our Faith by creating new spaces. (92-3) The new words that we bring into poetic representation can point us in the right social justice directions. With these “transfigural” visions, we must go back down the mountain to help. Dunaway translates Edwards’ title, Pour un christianisme intempestif: savoir entendre la Bible, to Untimely Christianity: Hearing the Bible in a Secular Age. “Untimely” here means that true Christianity is out of step with profit driven societies of Western Culture. Can “eternal,” meaning outside of time, be a substitute for “untimely”? We live in a prosaic linear time, getting things done Monday-Friday, but there is a more important poetic time where we stay on a vertical line pondering our existence. The Beatitudes sound vertical over the linear legalistic defined Commandments.

A major chapter on joy has Shakespeare’s Tempest as a background. A tempest is a major windstorm that gives the characters time to think. (41-5) Tempest has “temps” in it – meaning time and weather. All these words play on the title intempestif. A tempestuous, timely, untimely time to temper our thoughts while listening to the Bible, inspired by the Holy Spirit – the windstorm Trinity advocate.

Transfiguring Jesus as Poet and Teacher of His Prayer

With the Transfiguration, “eternity” changes Jesus into himself. (9-10) Dunaway notes that this is a citation of a Mallarmé poem “The Tomb of Edgar Poe,” where we hear that Poe’s works have stood up against blasphemies (accusations that his inspiration was from drugs). Time, “untimely” during his life, has helped us see his poetic transfiguration. Jesus, also, will be transfigured as my God. Jesus is a poet teaching us how to pray. Poetry requires a more sustained attention between poet and reader. (69) Between the poet and reader, we don’t really have one poet. There is another speaking that Edwards describes as the voice of the Holy Spirit. (69) A ghost writer? The “Our Father” transforms everything from the Fall of Humankind to the end of evil. (70) Word will become flesh. There is no “I” in Jesus’s teaching here. We need to be impersonal – to leave our egos, avoid temptation and help others. (73)

Jesus: Translator of God’s Transcendence

Since translation is such a major component of Scripture, we have to add it to the art of reading the Bible. The effective translator is also a writer, who, guided by love, helps us interpret meanings. Roland Barthes distinguishes between a readerly text, where one reads for information, and a writerly text (Bible included here) where the reader is active. (107) When reading or watching a thought-provoking-film, I always take notes and add my thoughts, which keeps me in the right disposition to interpret honestly.

Inspiration: Joy and the Transfiguration of Suffering

Edwards remarks that inspiration, theoretically and timewise, can only come from the early Hebrew and Greek texts. How then can we discern if a passage is from the Holy Spirit? “Delectation” is a word suggested by our “two translators.” In experiencing the Paschal Mystery of Death and Resurrection, Joy has to be mingled with sadness. We need to hear with our hearts. (157) Why do I prefer Good Friday to Easter? I should not, but it is while listening to Isaiah’s suffering servant and the Passion of Christ, followed by pondering the Cross that I enter in Communion with all my loved ones who have loved me when it was inconvenient to do so.

Faith above the law (without good works) is an idea of the Devil – not St. Paul. (25) We need to feel our way to God. (157) Doing the law does not necessarily mean knowing just the words. “You would not be seeking me if you had not found me.” (156) We are advised to hear with our hearts and to act as one cannot! (165) – acting as a responsible human for others and not self-seeking animals. God, through Pascal, puts these words in a convert’s mouth. “You would not be seeking me if you had not found me.” (156)

Joyful Rehearsal of our Mission at Mass

The word “joy” jumps across the Bible. It can mean charis that can mean both grace and thankfulness. There is a reflexive relation of Jesus and all us faithful as Jesus gives us grace to be good while we thank Jesus for this gift. (52) The Eucharist, or Mass, is the more definitive place where we carry on this thanking and then transfer our prayers to the real world. Michael Edwards and John Dunaway’s concept of God may be a little too “immanent” (near?) for me to relate to. However, the exposition of Jesus as the Sacrament of God allows me to be very comfortable and repentant at Mass. When asking for mercy and what to do, I pray these words, “My Lord and my God.”

(James Tomek is a retired language and literature professor at Delta State University who is currently a Lay Ecclesial Minister at Sacred Heart in Rosedale and also active in RCIA at Our Lady of Victories in Cleveland.)