By Stephen M. Colecchi (CNS)

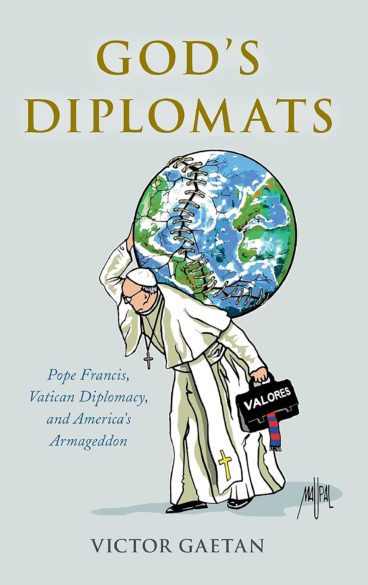

“God’s Diplomats: Pope Francis, Vatican Diplomacy and America’s Armageddon” by Victor Gaetan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers (Lanham, Maryland, 2021). 476 pp., $49.

Catholic social teaching has often been called the church’s best-kept secret.

In “God’s Diplomats,” Victor Gaetan illuminates its active application in the church’s international diplomacy and humanitarian work, unveiling another well-kept secret. He argues that the church’s dialogic approach to diplomacy contrasts sharply at many points with our nation’s more power-based and militaristic responses to international crises.

But his critique of U.S. foreign policy applies to many other nations and national leaders.

In Part 1, Gaetan contrasts U.S. and Vatican diplomacy. For me, the most poignant indictment of U.S. policy was the lead up to the invasion of Iraq, which occurred under St. John Paul II. The Holy See had warned that an invasion would stoke the fires of extremism, fan the flames of sectarian strife, contribute to regional instability and endanger the presence of Christians and other minorities in the region. All of this came to pass.

He goes on to describe the church’s diplomatic network, its mission for both the church and the common good of all and the education of formal Vatican diplomats. Gaetan explores the unique nature of the Catholic Church as a “sovereign” entity, describes its historical basis and then outlines its operating principles.

Although his focus is often on formal diplomats and seems at times clerical, it is clear from his accounts that the term “diplomats” includes many beyond the Vatican diplomatic corps and hierarchy. Men and women religious, lay men and women and numerous Catholic organizations and institutions are part of the church’s diplomatic network.

Unlike many commentators, Gaetan points out continuities among Pope Francis, Pope Benedict XVI and St. John Paul. Each has unique gifts and styles, but the long history of the Holy See’s diplomatic engagement is a thread that runs through their papacies. Gaetan’s love of the church, embrace of its teachings and respect for its leaders comes through clearly, even when he points out failures.

Gaetan makes a case for the effectiveness of what he calls the political “neutrality” of the church or what I might call its nonpartisan and nonaligned stances. He lifts up the church’s long-term patience, an unrelenting commitment to dialogue and a commitment to serving the common good.

His writing style captures complex diplomatic principles in accessible language. A good example is his diplomatic rules of thumb: 1) “Avoid creating winners and losers”; 2) “Remain impartial in the face of conflict”; 3) “Refrain from partisan conflict”; 4) “Pursue dialogue … with everyone”; and 5) “Walk the talk: Show faith through charity.”

The book’s second part explores specific international crises of recent years. Gaetan devotes a chapter each to Ukraine, Cuba, Kenya, Colombia, the Middle East, China and South Sudan.

I do not entirely agree with his understanding of the roles of Russia in Ukraine and the Middle East, but he is spot-on regarding the church’s various actors. Each international situation is well documented, giving credence to his analysis. I found the chapter on South Sudan particularly moving.

Gaetan has written a sympathetic and sweeping primer on the church’s diplomatic efforts. The author’s journalistic research is reflected in over 100 pages of footnotes that offer supplementary insights and anecdotes, lending credibility to his analysis. His extensive acknowledgments is a “who’s who” of key church diplomats.

“God’s Diplomats” will appeal to many audiences. It is a must read for secular diplomats and church leaders at every level engaged with the church’s diplomatic efforts. It should also be required reading for trained diplomats. In-the-pew Catholics and other people of goodwill will find it affirming of the positive role that religion can play in the public square.

Colecchi served as director of the Office of International Justice and Peace of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops from 2004 to 2018. In that role, he frequently engaged diplomats at every level of the church in many regions of the world.