From the Archives

By Mary Woodward

JACKSON – This article originally ran in Mississippi Catholic in Nov. 2016 when the mission church in Cranfield, St. John the Baptist, was celebrating its centennial. I am rerunning it to give a different flavor to this series from the archives. The story is connected to the eventual founding of Holy Family Church in Natchez and St. Francis School that we mentioned last article. After this lovely sidebar, we will return to the developing church in our state and race.

On Sunday, Nov. 6, 2016 a beautiful, fresh autumn day, more than 100 people gathered with Bishop Joseph Kopacz to mark the centennial of St. John the Baptist Mission at an early afternoon Mass. The small wood-framed church holds roughly 50 people. The overflow congregation was sheltered in a tent outside under the trees.

Shortly before the Mass was scheduled to begin at 1 p.m., a communicant arrived on a four-wheeler, reflecting the mission’s location to nearby hunting camps where many Louisiana Catholics come during hunting season. She zipped in and parked opposite the tents and took her place among the congregation.

The windows of the church were wide open, and the breeze of the day kept the natural flow of creation present as those gathered entered into the Divine Liturgy. The setting of the day brought us back to 100 years ago when Bishop John Gunn, SM, preached an eloquent sermon on the parable of the Good Samaritan likening the Cranfield mission to the protagonist who cared for the one in need.

The history of the mission is a prime example of a dedicated shepherd who traversed fields and valleys, climbed hills and braved thicket to find his flock. In his time Father Morrissey became known as the “Father of Missions” in the southwest corner of the diocese.

The Natchez ministry of Father Morrissey began in 1901 when he arrived at Holy Family Church. The parish was established in 1890 to serve African American Catholics in the Natchez area. Having been invited by Bishop Thomas Heslin, the Josephites have staffed Holy Family since 1895.

Under Father Morrissey, Holy Family soon became the mother church of four missions – Cranfield, Harriston, Laurel Park, and Springfield. On Monday mornings after his weekend duties at Holy Family, Father Morrissey would head out into the county in search of any Catholics and also those who were not church-going.

During his circuit, he often came upon Catholics who were not able to get into Natchez very often to receive the sacraments. This is where the story of Cranfield has its roots.

According to a history of the mission written in 1945 by Father Arthur Flanagan, SSJ, and pastor of Holy Family at the time, Father Morrissey came upon the Irish Catholic family of John Gordon Fleming. Fleming told Father Morrissey the family originally came from County Mayo, Ireland in the late 1870s. Fleming’s relative, Holiday Fleming, was the oldest son of the immigrants and brought with him his wife and children. The family would go to Mass in Natchez at St. Mary on Easter and Christmas – weather permitting. The children were all baptized and received sacraments from St. Mary.

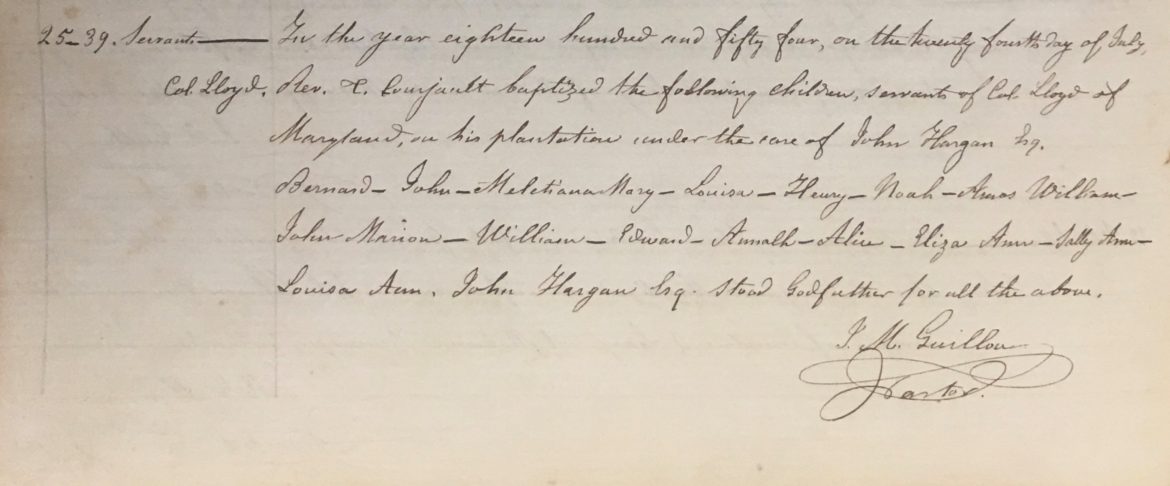

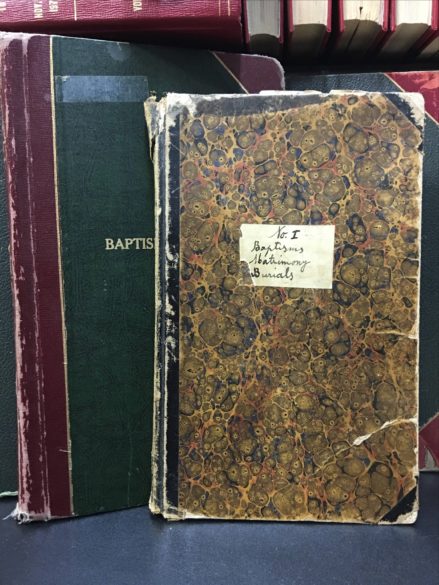

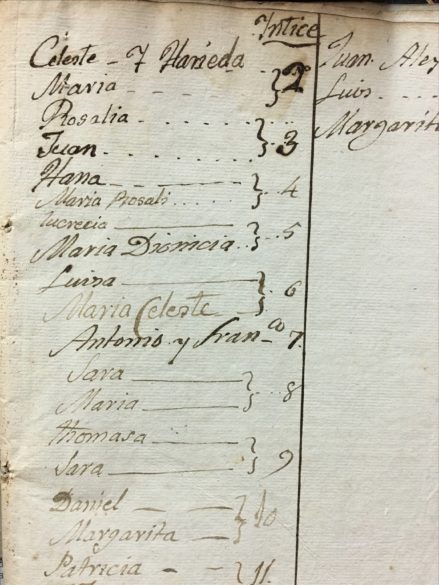

The next half of the story told by Fleming holds a true Mississippi cultural twist and a wonderful image of the people of God. Apparently, Holiday Fleming had been “true to his name, [and] went holidaying with the result that he was blessed” with a growing African American family. Father Morrissey saw the children and recognized they belonged to Holiday. Father Morrissey made sure these children were brought to Holy Family for sacraments and given their father’s name. Many Flemings can be found in the Holy Family sacramental registers.

Soon after meeting the Flemings, Father Morrissey laid plans to build a church in Cranfield. After a few years of saving pennies and nickels from various appeals, there was finally enough in hand to build the church on the land donated by Mrs. Boggart, a Catholic. The mission priest, along with the older African American Fleming children, built the church. As great artists often sign their masterpieces, Linda Floyd, granddaughter of Geraldine Fleming, a descendant of the original Fleming family, relayed that the young men who worked on the church inscribed their names in the steeple.

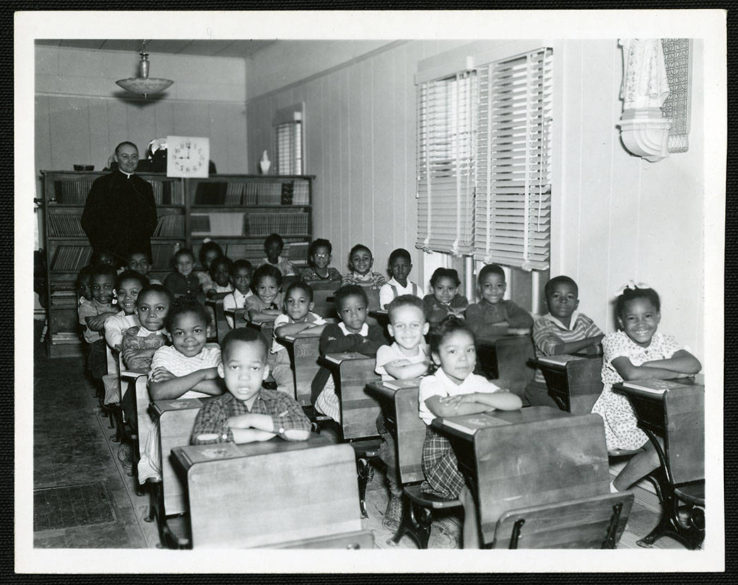

Initially, religious education taught by Rosie Washington was held in the church as there was no other building on the site. In 1938, a bus from Natchez came to bring the children to St. Francis School at Holy Family. On the weekend Mass was not celebrated in the mission, the bus was used to bring people to Mass at Holy Family.

As the years passed, the other three missions closed. Today Cranfield is the last of the four built by Father Morrissey. His missionary zeal reflects the true spirit of our diocese as a rural mission territory.

It was 100 years ago on Sept. 3, 1916, when Bishop John Gunn, SM, dedicated the mission church built by Father Matthew Morrissey, SSJ, and the Fleming family. Since then, many striking autumn days have filled the hearts and minds of the people of this unique mission. For those who live in larger parishes, a trip to Cranfield St. John the Baptist would be good for the Catholic soul.

(Mary Woodward is Chancellor and Archivist for the Diocese of Jackson.)