(NOTA: El Obispo José Kopacz cede su espacio para el análisis de esta intervención del Obispo Robert Barron, quien es el fundador de los Ministerios Católicos de Word on Fire y Obispo Auxiliar de la Arquidiócesis de Los Ángeles. También es el anfitrión de CATOLICISMO, un documental, innovador y galardonado, sobre la Fe Católica, que se emitió en PBS.)

Por Obispo Robert Barron

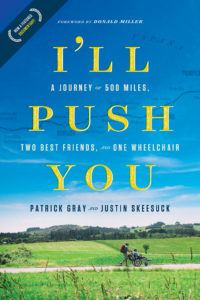

Bishop Robert Barron/Obispo Robert Barron

El encuentro de Jesús con dos antiguos discípulos en el camino a Emaús ofrece un hermoso ejemplo para el trabajo de acompañamiento de la Iglesia. El Señor camina con la pareja, incluso cuando estos se alejan de Jerusalén, y espiritualmente hablando, van en dirección equivocada. Él no comienza a juzgarlos, sino más bien presta atención y estimula silencioso. Pero luego, sabiendo que les falta toda la magnitud de la información, los reprende y luego informa “Y, empezando por Moisés y continuando por todos los profetas, les explicó lo que había sobre él en todas las Escrituras. “ Jesús escucha con amor y habla con fuerza y claridad.

Innumerables estudios en los últimos diez años han confirmado que los jóvenes mencionan razones intelectuales cuando se les pregunta qué los ha llevado a abandonar la Iglesia o perder la confianza en ella. Entre las principales hay convicciones como: la religión se opone a la ciencia o no puede resistir un examen racional, sus creencias están pasadas de moda, la Biblia no es confiable, las creencias religiosas dan lugar a la violencia o Dios es una amenaza para la libertad humana. Puedo verificar, por veinte años de ministerio de evangelización, que estas preocupaciones son obstáculos cruciales para la aceptación de la fe entre los jóvenes

Lo que se necesita vitalmente hoy, para el acompañamiento de los jóvenes, es una renovada catequesis y apologética. En algunos círculos de la Iglesia, el término apologética es sospechoso, e indica algo racionalista, agresivo, condescendiente. Espero que esté claro que el proselitismo arrogante no tiene cabida en nuestro alcance pastoral, pero espero que sea igualmente claro que es una explicación inteligente, respetuosa y culturalmente sensible de la fe. Existe un consenso entre personas pastorales, hemos experimentado una crisis en la catequesis, en los últimos cincuenta años.

Por lo tanto, ¿cómo sería una nueva apologética? Primero, surgiría de las preguntas que hacen los jóvenes espontáneamente. No se impondría desde arriba, sería una respuesta al anhelo de la mente y el corazón.

En segundo lugar, una nueva apologética debería profundizar en la relación entre religión y ciencia. Sin negar por un momento las ciencias, tenemos que demostrar que existen caminos no científicos y, sin embargo, eminentemente racionales que conducen hacia el conocimiento de lo real. La literatura, el drama, la filosofía, las bellas artes, todos primos cercanos de la religión, no solo entretienen y deleitan; también llevan verdades que no están disponibles de ninguna otra manera. Una apologética renovada debería cultivar estos enfoques.

En tercer lugar, nuestra apologética y catequesis deben recorrer la vía pulchritudinis, como lo caracterizó el Papa Francisco en Evangelii Gaudium y como argumentó Hans Urs von Balthasar, la belleza más convincente de todas es la de los santos. He encontrado una gran tracción evangélica en la presentación de las vidas de estos grandes amigos de Dios.

Cuando Jesús se explicó a los discípulos a Emaús, sus corazones comenzaron a arder. La Iglesia debe caminar con los jóvenes, escucharlos con atención y amor, y estar listos inteligentemente para dar “una razón para la esperanza que está dentro de nosotros”. Esto, confío, encenderá los corazones de los jóvenes.

(El obispo Barron ofreció esta intervención en el Vaticano, durante el Sínodo sobre los jóvenes, la fe y el discernimiento vocacional de 2018. Para obtener más contenido visite WordFromRome.com )