Por Fran Lavelle

El Año de la Eucaristía se inauguró en nuestra diócesis en la Fiesta de Cristo Rey y se celebrará hasta el año litúrgico 2022.

Nuestro tema, “Quédate con nosotros, Señor”, proviene del evangelio de Lucas (Lc 24: 13-49) al que se hace referencia como la historia de Emaús. En él escuchamos acerca de dos discípulos, de camino a Emaús, hablando de los recientes acontecimientos en Jerusalén. Jesús se encontró con los dos en el camino y habló con ellos mientras continuaban su viaje, aunque no lo reconocieron. Al acercarse la noche, instaron a Jesús a que se quedara con ellos. Mientras estaba a la mesa, Jesús tomó pan, lo bendijo, lo partió y se lo dio. Con eso se les abrieron los ojos y reconocieron a Jesús.

“El viaje más largo es de la cabeza al corazón”

Un elemento central de la historia de Emaús es el viaje de los dos discípulos. No solo el viaje físico de Jerusalén a Emaús, sino el viaje de fe y creencia en Cristo resucitado. Hay un viejo dicho atribuido a los indios Sioux: “El viaje más largo es de la cabeza al corazón”. Esto es cierto especialmente cuando se trata de asuntos de fe. Nuestra capacidad de creer en lo que no vemos y lo que no entendemos requiere mucha confianza y fe. Creer y comprender la Eucaristía es una de esas cosas que requiere una gran fe y confianza.

Si no ha considerado su deseo al recibir la Comunión en la Misa, le invito a que lo haga. Un sacerdote de Kentucky, amigo favorito, les recordaría a sus feligreses con regularidad que debemos chequearnos para asegurarnos que nos estamos volviendo un poco en lo que recibimos, que es Jesús. Si nuestra respuesta es no, debemos considerar por qué no. Si nuestra respuesta es sí, debemos pedirle a Dios la gracia de seguir siendo transformados por la Eucaristía.

Para encontrar un mayor significado en los aspectos devocionales del Año de la Eucaristía, es oportuno centrarnos en nuestra comprensión personal de la Eucaristía. No importa cuántos años tengas o cuántos años hayas comulgado, haz que éste sea el año en el que te sumerjas más profundamente. Hay muchos, grandes libros, escritos sobre el tema por muchos teólogos dignos, desde la Summa Theologiae de Santo Tomás de Aquino hasta estudios más modernos como La Eucaristía: Sacramento del Reino de Alexander Schememann o el libro más reciente del Obispo Barron simplemente titulado Eucaristía. El punto es leer algo que te ayude a seguir siendo transformado por la Eucaristía.

Otra idea es pensar en cómo estamos presentes durante la Misa. Cuando estaba trabajando en mi maestría, tomé un curso sobre las oraciones eucarísticas. Antes de ese curso, nunca los había leído independientemente de la Misa. Hicimos una combinación de exégesis y Lectio Divina del texto. Al hacerlo, me di cuenta del texto de una manera más completa y que más me resonó. Me abrió una comprensión y una forma de pensar completamente nuevas sobre la Eucaristía. Entonces, en lugar de suspirar cuando el sacerdote comenzó la primera plegaria eucarística pensando que era larga, llegué a apreciar el mensaje lleno de esperanza que cada oración transmite de manera única.

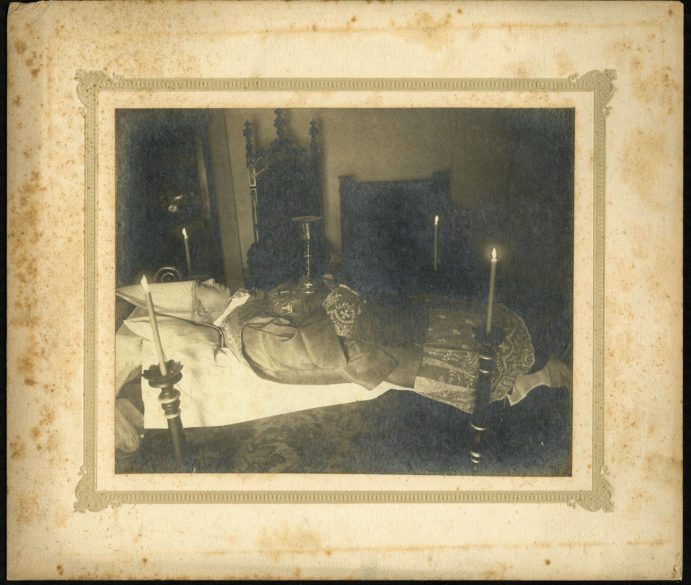

El Año de la Eucaristía

En este año habrá devociones externas como procesiones eucarísticas, exposición y adoración y un Congreso Eucarístico diocesano. Todas estas, expresiones excepcionalmente buenas de fe y amor.

Pero también podemos realizar pequeños actos personales que nos acerquen a Jesús en la Eucaristía. Por ejemplo, ser consciente de cómo tratamos a las personas en el estacionamiento después de la Misa.

Cuando vivía en el norte de Virginia, siempre me asombraba que necesitáramos que la policía local nos ayudara a navegar el tráfico después de la Misa. Quiero decir, ¡ya teníamos el incentivo para ser amables los unos con los otros!, minutos después que varios cientos de personas acabaran de recibir a Jesús!

Es apropiado que digamos: ¡Quédate con nosotros, Señor! Quédate con nosotros más allá del rito de la despedida. Quédate con nosotros en nuestros autos, en el restaurante cuando comemos y cuando empecemos la nueva semana, ya sea en la escuela, el trabajo o en casa. ¡Quédate con nosotros, Señor! cuando estemos en las redes sociales, en eventos deportivos y en los lugares comunes en los que nos encontramos cada día. ¡Quédate con nosotros, Señor! y juntos podemos llegar a ser como tú. Dejemos que la Eucaristía sea el espejo que sostenemos para vernos crecer y ser un poco más como Jesús.