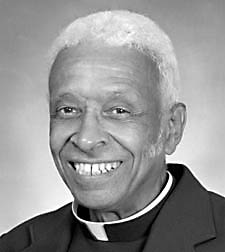

Melvin Arrington, Jr.

Guest Column

By Melvin Arrington, Jr.

“Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that . . . Old Marley was as dead as a doornail.” What little boy with a fertile imagination would not become hooked on those opening lines?

More to the point, how could a child know that a tale about death and ghosts was really about divine mercy and metanoia (repentance and the redirection of one’s life toward Christ), if not for a big person to guide him to an understanding of the spiritual truths conveyed by the story?

I was the little boy, the guide was my daddy, the time was one Christmas in the late 1950s, probably 1958, and the book was, of course, Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. That year Santa Claus brought me, in addition to a few toys long since forgotten, a brand new edition of Dickens’ classic story published by Grosset and Dunlap and visually enhanced by sixteen unforgettable color illustrations by Libico Maraja. At that point I was just beginning to leave comic books behind. That hardcover volume was one of my first “real” books.

Almost 60 Christmases have come and gone and I still have that copy of A Christmas Carol. Considering its age, it’s still in pretty good condition. I think I can truthfully say that it has held up better than I have.

The period from Thanksgiving to year’s end was always a happy, joyful time in our family. I think my parents looked forward to Christmas almost as much as my little sister and I. Mama liked to spend time in the kitchen preparing holiday meals, and Daddy enjoyed getting everyone in the Christmas spirit by telling the story of Old Scrooge.

Why did my father take such a special interest in Scrooge? I knew that following his service in the Pacific during World War II he had returned home, married and started a family, like so many young men of his generation.

But during those post-war years he found himself moving further and further away from God, and he stopped attending church. He was never a hateful old miser like Scrooge, but he had let sin dominate his life. Then in the spring of 1957 he had a profound life-altering conversion experience. It was several years later when I came to understand that Daddy liked Dickens’ story so much because in many ways it mirrored his own transformation.

Christianity is a religion of second chances.Scrooge, in revisiting all the times in the past when he failed to be charitable eventually realized that his life was not about himself. Daddy made a similar discovery. Given a second chance he, like Scrooge, responded to the call to metanoia and became a new person.

I’m thankful that Santa Claus brought me a copy of A Christmas Carol that year. Books have been an important part of my life ever since, and that one has brought me great joy because of the wonderful memories it evokes of my daddy.

(Melvin Arrington is a Professor Emeritus of Modern Languages for the University of Mississippi and a member of Oxford St. John Parish.)